These national data show the necessary course, but we also anticipate uneven demand development across the United States, particularly in states where EV adoption is already very robust. Under the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, which has 35 states as signatories, $7.5 billion is designated for EV charging infrastructure. The building of 500,000 charging stations has been promised by President Biden, but that is just the beginning.

McIlravey took note: “The faster growth of customer demand will drive private investment and more rapid deployment of charging infrastructure in jurisdictions that are adopting the California Air Resources Board’s strategy for selling zero-emissions vehicles (ZEVs). But, development of charging stations won’t need to happen as quickly in places where EV adoption comes gradually, and it might also need a little push.”

Development of an EV charging infrastructure may be more dependent in slower-to-adopt jurisdictions on the spark of public-private investment to propel it slightly ahead of actual demand.

California, Florida, Texas, and New York generally have the greatest numbers of registered new vehicles and operating vehicles in the United States. California is the state promoting the strictest pollution regulations since it adopted EVs first. With about 36.9% of all EVs now in use and 35.8% of all US light-vehicle EV registrations from January through September 2022, it is the largest EV market.

Also, the weather in these states is mostly conducive to EV use. There is little doubt that the necessary investment will be made in these markets given the top-down (government) and bottom-up (consumers and charging network operators) support for development in order for the United States to achieve its target for EV adoption. The power of ZEV states will continue to be important to EV growth as EV adoption grows in the United States. Yet, there will need to be enough public charging infrastructure to support users in the sizable markets outside of the ZEV states.

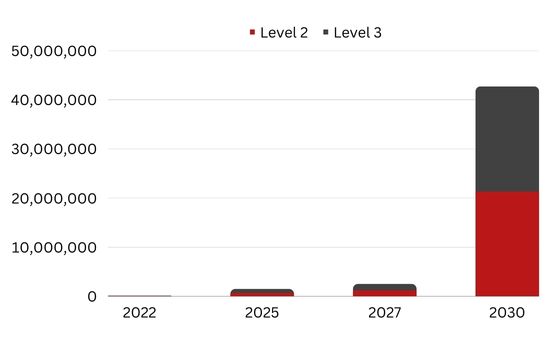

Texas presently has roughly 5,600 non-Tesla Level 2 chargers and 900 Level 3 chargers, but according to a prediction from S&P Global Mobility, by 2027, the state will require about 87,500 Level 2 and 7,800 Level 3 chargers to accommodate the anticipated 1.1 million EV VIO.

Florida now has 955 Level 3 chargers and around 5,600 Level 2 non-Tesla chargers, but by 2027, it is anticipated to have 1.06 million potential EV VIOs. S&P Global Mobility predicts that Florida will need to expand its charging infrastructure to around 77,000 Level 2 and 6,800 Level 3 charging stations in order to accommodate these vehicles.

Outside of big metro markets, there is still a smaller investment being made in charging infrastructure. Even though EV adoption in those regions will remain more slowly, there is still a need to build a strong infrastructure. 85% of Level 3 charges and 89% of Level 2 chargers are now located in US Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs, as defined by the US Census Bureau and includes 384 metro regions). For Tesla owners, 83% of destination chargers and 82% of Superchargers are located in MSAs.

As the number of operating vehicles rises and users needs access to charging stations along their travels, McIlravey said, “the concentration on urban areas follows where EVs are today.”

Several industry experts view the gas station as a model that can be used to recharge electric vehicles. Yet, a comprehensive charging infrastructure will look very different from the network of gas stations that have developed to support the internal combustion engine because at-home charging is typically the simplest approach to integrating an EV into daily life.

Faster charge times for DC or Level 3 scenarios are being made possible by advances in EV chargers, battery management systems, and battery technologies, which may have an impact on where charging stations are placed.

There are also adapting solutions that can alter the model. Increasing the use of DC wall box solutions in homes, wireless charging, and battery swapping are three technologies that have the potential to alter the environment. Battery swapping is a growing and somewhat successful technique in China, but it has received little attention outside of the initial NIO stations in Norway and has not yet been thoroughly tried (or anticipated) on the American market.

The need to homogenize battery packs, which would require OEMs and Tier 1 suppliers to give up some of their intellectual property, as well as the preference for home charging are the factors holding back a technology like battery swapping, according to Graham Evans, director of S&P Global Mobility research and analysis.

According to Evans, the widespread use of wireless charging has the potential to end the existing conflict between battery size and range. Evans claims that if dynamic wireless charging becomes widely used, users will be able to charge more conveniently at home and adopt “splash and dash” habits. Evans admonished that the price of wireless charging would be a problem and that mainstream consumers might not be eager to pay more for it. The deployment of wireless charging must now play catch-up even though plug-in technology came first to emerge and was less expensive, despite the fact that it may be more convenient.

At-home DC wall box solutions are the third technology that could upend our presumptions. Evans claims that they provide a middle ground between the slow AC chargers and the incredibly rapid public DC charges. The balance between household and public charging may change if these methods are used more widely. Additionally, there are models that enable V2G (vehicle-to-grid) operation, which has the potential to shift the debate by enabling EVs to practically integrate with our electrical grid system and generate some revenue for participating consumers.

The refueling system is changing along with the automotive industry in the US as it moves from internal combustion to battery-powered vehicles.

“The recharging infrastructure must do more than keep pace with EV sales,” Evans added, “for mass-market acceptance of BEVs to take hold.” “It must astonish and excite car owners who are unfamiliar with electrification such that the process seems flawless and might even be more convenient than their experience with filling up with gasoline, with the least amount of disruption to the car-owning experience. Improvements in this area will depend just as much on advances in battery technology as they will on how rapidly infrastructure can supply electricity to EVs.”